RESULT AND IMPACT INDICATORS

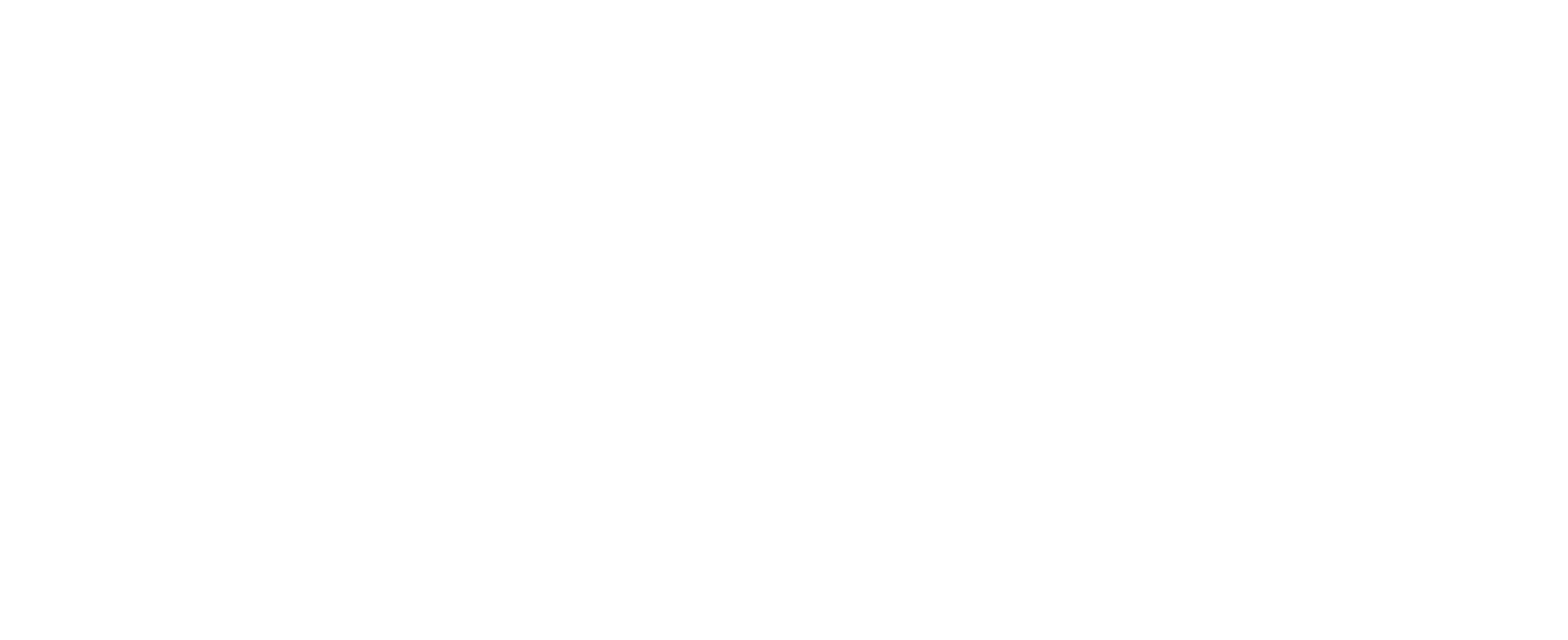

The project activities contributed to the results related to the “sustainable production” component (2) of the Amazon Fund Logical Framework.

Direct effect 1.1: economic activities of sustainable use of forest, agroforestry and biodiversity developed

Direct effect 1.2: chains of agroforestry products and biodiversity with increased added value

The main indicators agreed for the monitoring of this objective were:

- Annual revenue from sustainable use economic activity – in natura products (outcome indicator)

Goal: not set | Result achieved: R$ 78,500.00

- Annual revenue from sustainable use economic activity – processed products (R$) (outcome indicator)

Goal: not set | Result achieved: R$ 409,121.00

Agroforestry products were commercialized as a result of the project’s actions, namely: banana, pineapple, coconut, orange, watermelon, açaí berry, cassava and corn. However, the main revenue was generated by activities that added some value to

in natura products, such as the commercialization of cassava flour. The baselines of the in natura and processed products (2015) were, respectively, R$ 20,000.00 and R$ 84,500.00. The results achieved refer to 2017. It is worth mentioning that the portion of the production that is consumed by the indigenous persons themselves (food security) was not measured by this indicator, because it is not commercialized.

- Recovered area used for economic purposes (outcome indicator)

Goal: 170 ha | Result achieved: 238 ha

Deforested areas recovered by the implementation or enrichment of AFSs contributed to diversify the food of indigenous families, ensuring their food security by means of food production and income generation with the commercialization of surpluses.

Direct effect 1.3: expanded managerial and technical capacities for the implementation of economic activities of sustainable use of forest and biodiversity

- Indigenous persons trained to practice and manage sustainable economic activities that effectively apply the knowledge acquired (outcome indicator)

Goal: not set | Result achieved: 88

The result achieved – 88 trained – covers individuals who effectively apply the acquired knowledge, who were trained in the two training courses of indigenous agroforestry agents and in the other training activities promoted by the project (exchanges and advisory).

Institutional and administrative aspects

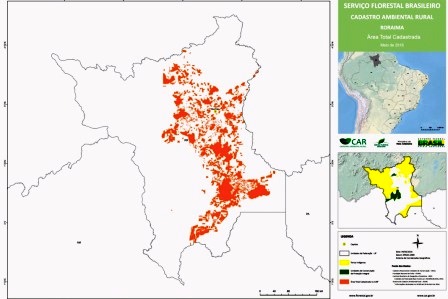

Partnerships were established with four indigenous associations, representatives of the indigenous peoples of the four TIs benefited by the project, namely: (i) Upper Purus River Huni Kuin Indigenous People Organization (Opiharp); (ii) Yawanawa Sociocultural Association (Ascy); (iii) Humaitá Igarapé Shawadawa People Association (APSIH); and (iv) Humaitá River Indigenous People Association (ASPIRH).

The representatives of these associations participated in the planning and part of the execution of project activities in their TIs. These representatives also participated in their monitoring, following the work of the indigenous agroforestry agent hired for

each TI and participating in the monitoring and evaluation of the project throughout its implementation. Holding project monitoring and assessment meetings at each new stage of its implementation also contributed to develop the organizational capacity of partner indigenous associations.

A partnership was established with the Department of Agroforestry Extension and Production (Seaprof) of the state of Acre to support the transportation between municipalities of the materials to be taken to the TIs and to provide a technical specialist

in fish farming and a technical specialist in meliponiculture who mediated thematic workshops within the project.

Risks and lessons learned

Despite the relevant results achieved by the project, some challenges faced are highlighted whose corrective measures can be understood as lessons and recommendations for similar projects.

To implement the rearing and management of chelonians and fish, four weirs were built in two of the four TIs benefiting from project actions. The planned activities were carried out late, because of the time-consuming process to obtain response from the competent environmental agency on their environmental licensing.

The lesson learned is the recommendation that when a project provides for activities that need to start an environmental licensing process (even if it is to be exempted from this licensing), it is important to start the coordination with the competent agencies as soon as possible so as not to compromise the execution of the activity.

The objective of developing the honey value chain was partially achieved, as the project concentrated greater efforts on the training and installation of meliponaries, that is, in some of the stages of the chain, however, it did not delve into the development of the product for commercialization.

The prospect is that bee keeping and honey production will evolve, due to the great interest shown by the indigenous people and their ease to learn how to manage native bees. The major challenge will be the commercialization of honey, as there are specific sanitary standards for it to be marketed. Nevertheless, indigenous families and children benefited from the theme of food security, because, with the project, their access to this nutritious and medicinal food was expanded.

The team responsible for the project execution realized the need to further involve the administrative team in the planning of their activities, so they had a better understanding of the materials to be acquired for executing the planned activities.

A positive practice adopted by the project, motivated by the precarious logistics of the Amazon, is to create conditions so the performance of activities depend minimally on external inputs. In the implementation of the AFSs, one of the measures adopted was to invest in the production of seedlings in the TIs benefited by the project, thus reducing the need to bring seedlings from afar.

This strategy circumvented the difficulty of finding fruit seedlings in the municipalities near the TIs, as well as shortened the path between the nurseries and the AFS areas, reducing the challenge of river transport, which needs to respect several variables, such as the weight in the vessels, the water level in the rivers and the damage caused to the seedlings by the sun and wind during their transport.

It is also important to include and maintain constant dialogue with representatives of the beneficiary communities, consulting them and considering joint strategies to overcome challenges and/or make any proposal more efficient. For example, the activity with the AFSs took place differently from what was expected, with regard to the size of planting by TI, due to the observance, throughout the project, as to the vocation of each community and the corresponding demonstration of commitment to a given activity, which was unveiled with the evolution of the activities. This is an important and sensitive perception that projects of this nature must foster, seeking the balance between the promotion of new practices and respect for the characteristic designs of each community.

Regarding the government procurement programs PAA and Pnae, it was not possible to perform, comprehensively, the registration of indigenous producers interested in marketing. To access these programs it is necessary to obtain a Pronaf Fitness Statement (DAP). And the DAP was not issued for most TIs due to operational difficulties, such as availability of system and technicians trained by the municipalities to serve the indigenous population, in addition to the minimum requirements not adhering to the local reality. The issuance of DAP was possible only in the municipality of Santa Rosa do

Purus, for some of the beneficiaries of the project, allowing the commercialization of production for school meal.

Sustainability of the results

The project had the merit of directly benefiting 974 indigenous people, of which 362 were women. Among the main impacts observed, we highlight the increase in agroforestry production, the expansion of cassava processing, the commercialization

of these products, the training of indigenous families for new productive activities and the training of indigenous agroforestry agents. It is estimated that these positive impacts are sustainable, because in addition to ensuring food security they also provide an economic alternative.

The initial investment in inputs, tools and machines enhanced agroforestry production and other productive activities supported by the project, which were also benefited by technical assistance and training.

Efforts were also made so that indigenous associations and families benefited understood the importance of being responsible for all material goods granted to them, ensuring their proper use and proper maintenance. One of the challenges is that they realize, over time, the need to reinvest resources in the tools and inputs needed to continue with the strengthened production, ensuring the sustainability of these productive activities and their economic autonomy.